By Claire Downing (Program Officer) and Deborah Makari (Program Assistant)

Updated on July 23, 2020.

On July 22nd, the House passed the NO BAN Act 233-183, taking the first step towards striking down the Muslim/African and refugee bans. Organizations representing Muslim, Arab, South Asian, and African communities are continuing to strategize over next steps, although the bill is unlikely to be taken up in the Senate. Likely paths forward include exploring alternative methods to repeal the ban including through appropriations processes.

Background

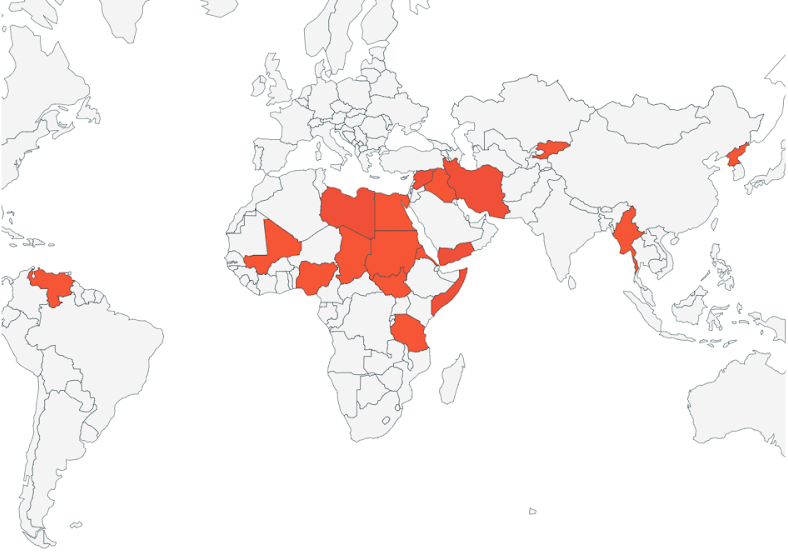

June 26, 2020 marked the two-year anniversary of the Supreme Court decision (5-4) to uphold the Muslim ban enacted by the Trump administration (Trump v. Hawaii). Since this landmark decision, the Trump administration further expanded the policy in January 2020, to include Burma (Myanmar), Eritrea, Kyrgyzstan, Nigeria, Sudan, and Tanzania. (The list of countries in the SCOTUS case was Sudan, Somalia, Yemen, Libya, Iran, Venezuela, and North Korea.) The policy as a whole is now referred to as the Muslim/African ban, highlighting the targeted nature of the policy and the administration’s intent to further a white supremacist agenda. For more details on the history of the different iterations of the bans and the work Muslim, Arab, and South Asian groups and partners are doing to reverse this policy, refer to the National Immigration Law Canter’s (NILC) piece, “One Year After the SCOTUS Ruling”. In this post we outline some of the recent developments on the ban’s expansion and offer some lessons learned from our support to organizations seeking to rescind the harmful policy .

Updates: New Realities Under COVID-19

The NO BAN Act, the only current bill dedicated to repealing the Muslim/African and refugee bans and championed by a variety of Muslim, Arab, South Asian, and African groups, was up for a floor vote in the House of Representatives as the COVID-19 pandemic was ramping up in the U.S. As such, House leadership postponed the vote, but the vote has now been rescheduled for July 22nd. The NO BAN Act seeks to repeal all versions of the Muslim/African, asylum, and refugee bans; prohibit future immigration policy discrimination based on religion; and curtail executive authority to prevent future presidents from enacting similar policies. Depending on the outcome of the vote, groups in the Muslim, Arab, South Asian, and African space are also continuing to strategize over alternative ways to repeal the ban. Further, since the COVID-19 pandemic began, the administration has put in place additional travel and immigration restrictions under the guise of mitigating the virus spread. However, in line with the administration’s policy track record, the objective is to limit the entry of individuals from other countries and further the myth that immigrants hinder the U.S. economy. These policies are worrisome especially when considering their long-term impacts and how restrictions on Black and Brown individuals are likely to remain after the pandemic has subsided, under the guise of public safety. Beacuse they have strategized and engaged with the legal system for years on the Muslim/African ban, Muslim, Arab, South Asian and African communities are essential in developing tactics to advocate for re-opening the country to immigration.

Lessons Learned

RTF has learned several lessons throughout our continued support of the Muslim, Arab, and South Asian field to fight back against the iterations of the Muslim/African ban, starting with the first Executive Order and airport protests in January 2017, through to the ban’s expansion in early 2020, and the second anniversary of the SCOTUS decision:

1. Support grassroots mobilization and policy change: While early funding from philanthropy largely focused on litigation, RTF has taken a comprehensive approach to pushing back against the ban. Our strategy recognized the need to shift public opinion on how Muslims, Black immigrants, and other people of color are securitized under the guise of national security, foreign policy, and immigration. To that end, RTF has funded a variety of grassroots organizing efforts to push back against the Muslim ban, including demonstrations, public education efforts, and arts and culture-based efforts. (Read more about our grants here.) RTF’s c4 sister organization, the RISE Together Action Fund, has funded nearly $100,000 in lobbying and legislative advocacy efforts to pass the NO BAN Act and rescind the Muslim/African and refugee bans.

2. Elevate and center Black-led perspectives and work: From the outset, the various iterations of the Muslim/African ban have focused on the most vulnerable, from blocking citizens from war-torn Yemen and Libya to preventing those facing life-threatening diseases from entering the country for treatment. But the expansion of the ban in 2020 to include mostly Black African countries (in addition to Somali and Sudan, on the original list) made it clear that this wasn’t just a Muslim ban, but an African ban, and that the intent was to block Black people and people of color from entering the country. While the original ban affected 135 million people in 7 countries, the expanded ban affects nearly a quarter of the African continent’s 1.2 billion people.

As part of our commitment to increasing our support for Black-led work, we have worked with the Muslim, Arab, and South Asian Organizing team and our grantee ReThink Media to incorporate Black-led groups affected by the ban into monthly calls and outreach, including on messaging that this is both an African and a Muslim ban. This has led to a more informed and nuanced messaging from the field on the anti-Black nature of the ban, and elevated new partnerships among Black-led and Muslim, Arab, and South Asian groups. Our February blog post, “Standing in Solidarity to Fight Anti-Black Racism”, points to the need for recognizing how interwoven our inequities are and the importance of working in tandem to further understand the struggle of the most marginalized and dismantle our unjust systems.

3. Investment in communications capacity makes a difference: RTF has been investing in a shared communications hub model for the field since 2010 through grants to ReThink Media’s Rights and Inclusion team. In addition to ReThink’s messaging on the ban, their op-ed placement and ghostwriting on the ban’s impact have led to public pressure on officials to take up individual cases which then led to relief for impacted individuals. For example, ReThink’s work with the Courier Journal in Kentucky, highlighting the plight of an Iranian woman denied entry into the U.S. for life-saving medical care, eventually led to the woman’s visa being approved and her receiving the needed care; this highlights the power of media engagement to create awareness, pressure, and ultimately change.

How Can Philanthropy RISE to the Occasion?

In RTF’s work and conversations with funders, we have not seen widespread dedication to rescinding the ban or dealing with its effects of family separation. Here’s how we can change this: While the ban remains in place, there are several concrete ways that philanthropy can help build public pressure for rescinding the ban:

1. Elevate the Muslim/African ban as a top immigration priority: Ensure that funding towards immigration policy reform centers Muslim, Arab, South Asian, and African voices. Incorporate these perspectives into funding for policy advocacy and public education on legislation. Review your portfolio and see if you are funding these groups already. If so, can you increase funding for this work? If not, what would it take for you to fund this work? The Muslim/African ban continues to be one of the administration’s longest lasting and cruelest policies, and communities continue to need support for immigration relief on this issue. For example, the Bridge Initiative found that from FY16-19, “of all refugees resettled in the U.S., there was a decrease of Muslims resettled by 90%.” If you fund immigration policy work, are you funding Muslim, Arab, South Asian, and African organizations, too? The Muslim/African ban is an immigration issue.

2. Recognize the ban as a family separation tactic: In 2019, the Bridge Center analyzed visa data on the ban and of the cases reviewed, found that 26% were children separated from parents, and 37.7% were partners separated from each other. Therefore, ensure that conversations on family separation tactics address how the ban has affected families in the U.S. and abroad. Center two of the ban’s most damaging effects – impacts on mental health and physical health through separating families and through denying access to medical care.

3. Incorporate the perspectives of affected communities into conversations, programming, and grantmaking: Invite a member of an affected community, or an organization representing said communities, to speak about the ban on your panel or other programming. And, if you’re continually calling on them for expertise on the ban, consider supporting their work financially to compensate for their intellectual and emotional labor.

4. Join the Proteus Fund and RTF in signing on to GCIR’s statement, “Philanthropy Must Confront Our Country’s History of Racist Immigration Policies”.

The Muslim and African Bans: By the Numbers – Bridge Initiative at Georgetown University

The Muslim and African Bans – Bridge Initiative at Georgetown University

From Bigotry to Ban: The Ideological Origins and Devastating Harms of the Muslim and African Bans

No Muslim Ban Ever Campaign – SCOTUS #NMBE #RTB Anniversary Digital Toolkit

Muslim Advocates – Talking Points, COVID Rebuttal, Resources Doc